Not so long ago, images from Bergamo, Italy, which showed how military transporters carried away the corona corpses in crematoria, shocked. The reason: many elderly people in particular fall ill and overburden the health systems, especially in Italy. But the ageing of society in Europe is not only evident during the current corona crisis. Above all, it is causing economic problems throughout Europe that will last longer than the corona pandemic. Slowly but surely, the effects are becoming clear and are creating potential for tension between the EU states.

May 5th 2020

By Andreas Würtz Adamsen and Caroline Kleine-Besten

Olivia Neagoie, 21, from Timișoara in Western Romania, is in the second year of her Bachelor’s degree in “Digital Media” and has made a decision. As soon as she finishes her Bachelor next year, she wants to emigrate to Sweden: „I already have sort of love relationship with Sweden as a whole country but mostly about the culture, the professional people […] and the professional way of jobs there […]. Of course, I prefer to be close to my family and to my friends at home, but I also want to have a decent salary and a decent way of life.”

Overall, Olivia’s decision describes only part of the problem that will occupy the EU for some years to come. Behind the term “demographic change” are clear figures on population growth, ageing, and migration, which do not give the EU a good forecast.

Prospects for developments and consequences in the EU

Fact box: According to Statista, Italy is the oldest EU country with an average age of 46 years, Ireland the youngest with an average age of 37 years.

According to a 2019 report by the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), the EU currently has a population of around 500 million, or 6.9% of the world’s population, but this figure will fall to 4.1% by the end of the century. In addition, low birth rates and increased life expectancy mean that the average age of the population is getting older and older. In 2001, the average age was 38.3 years, in 2018, it will be 43,1 years, according to Statista.

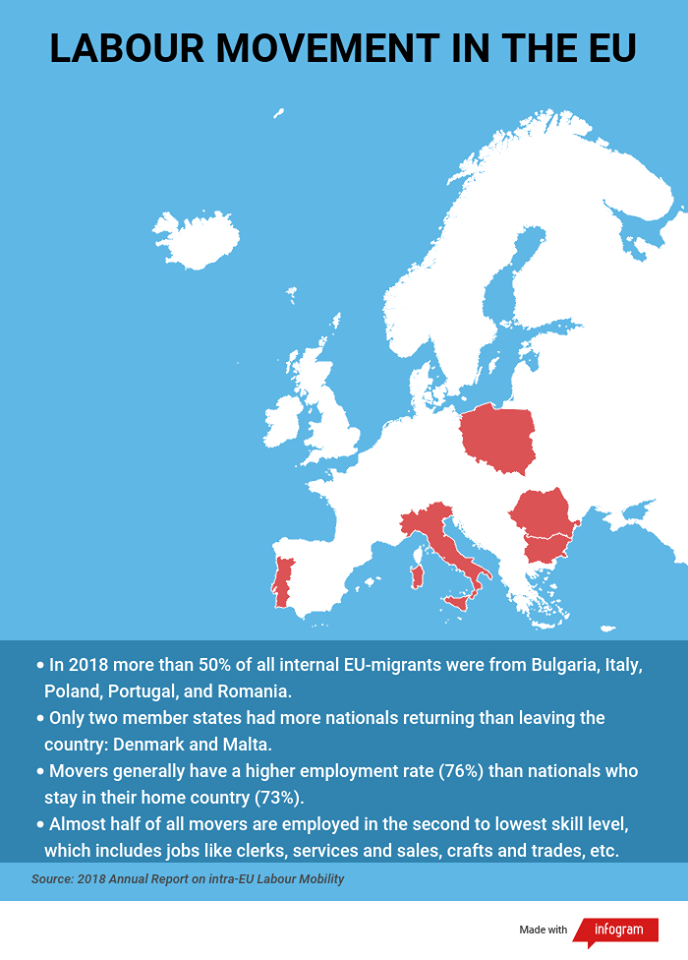

The consequences of this development are already visible now and become clear in the EPRS report. Especially in more rural EU regions, the population is decreasing considerably, which further aggravates the economic problems these regions often have to deal with anyway. The younger people who still live there are generally more likely to be attracted to where they are offered good work and career options, which is often only found in the larger cities of a country or abroad. Due to the free movement of labour within the EU, applications for residence permits are increasing, especially in the economically stronger countries such as Poland, Germany, France, and Sweden. Thus, the EU countries have to compete more and more for educated workers. The consequence is clear: the gap between town and country, rich and poor, young and old is widening.

In a written interview, Dubravka Šuica, Vice-President for Democracy and Demography at the EU commission, makes it clear: “This is not a phenomenon limited to a certain geography. At the same time, some of the member states that are attracting a lot of labour force still age quickly, for example Germany.”

The European Committees of Regions presented proposals to the EU Commission

Fact box: The European Committee of the Regions (CoR) is the assembly of regional and local representatives of the EU, which gives the respective regions, districts, provinces, cities and municipalities a direct voice in the EU’s institutional structure.

Only recently, János Ádám Karácsony (Hungary), representing the European Committees of Regions (CoR) as a rapporteur, introduced proposals to the EU Commission on how to measure and manage negative impacts in EU regions. This is just one of the countless documents in which various EU institutions deal with the problem for many years. Proactive measures against this development include, for example, the promotion of family-friendly policies to increase the birth rate, targeted investments in infrastructure, culture and networking of rural regions, improving the labour market participation of women in particular, reducing health and care costs, but also adapting to the transition to an older EU.

In accordance with the CoR, Karácsony emphasises in an interview the efforts required in the above-mentioned aspects in the more rural areas to maintain the connection between urban and rural areas. He also sees this as important for democracy and refers to a passage from the mission letter written by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to Vice-President Dubravka Šuica: „Those who feel left behind by progress and transition are the ones most likely to become disaffected. The root cause of this for many is more about demographic change than democratic structures.”

Dubravka Šuica explains the procedures of the EU-Commission in this context: “The Commission’s portfolio on Demography is rather about understanding demographic trends, anticipating impacts and closing the gaps on the labour market. […] Demographic change is per se not something that can or must be stopped. Instead, we need to observe, analyse and anticipate the change so that we can adjust and adapt our policies and initiatives to the new European realities.”

All facets of demographic change are becoming apparent in Romania

Olivia’s home country Romania is one of the countries where more needs to be done than in other EU countries. As a study by the Berlin Institute for Population and Development from 2017 shows, the strong agricultural sector in the regional areas with 3.6 million farms provides work, but not enough pay. The GDP per capita here does not even reach one-third of the urban level. It is precisely for this reason that many young Romanians are attracted to the big cities, such as Bucharest or Cluj-Napoca, where computer scientists are in particular demand, which increases the gap.

Dr. Martin Sieg, head of the Romanian office of the German Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, which is working worldwide for the political consolidation of democracy, states: ” What has developed quite well in the past is the whole IT sector, including infrastructure; compared to the internet access and speed here, Germany is far behind”. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of jobs in this sector increased by almost 50,000, according to the study of the Berlin Institute.

In other sectors, however, despite the big city, things are more difficult, as Olivia reports: “I wanted to get a job this year and I have currently send about 36 CVs to the companies. […] And from those 36 CVs I only received back two phone calls, which kind of proves me that the working environment in Romania is not the most reliable. In Sweden I received an answer in one week […].

Thus, in addition to the rural exodus, Romania has long suffered from labour shortages, particularly in the education and health sectors, due to a combination of demographic change and migration. According to the study by the Berlin Institute for Population and Development from 2017, the number of inhabitants in Romania has shrunk from 21.5 million to currently 19.4 million since Romania joined the EU in 2007. This means that no other country has lost more people than Romania after Latvia and Lithuania. In 2040, Romania is likely to be one of the oldest countries in the EU.

This often raises the question whether migration from abroad could not solve the problem. Here, however, Mr. Sieg finds clear words: “What Romania is losing within the EU are many well-educated people, who follow opportunities for their own development and income. If the country itself is not yet able to keep these people, it does not seem to make much sense to seek compensation by immigration.”

Unfortunately, despite several attempts, we did not receive a statement from the Romanian government on the measures taken to mitigate demographic change.

Vice-President appeals for cohesion between EU countries

With regard to possible tensions within the EU due to increasing labour shortages, Vice-President Šuica emphasised: „We are a Union. Hence, we need to ensure that we do not leave anyone behind. This means that some regions who are suffering from a strong depopulation do not enter a vicious cycle of becoming empty and in the end unable to offer attractive living conditions. […] In the end, all of us – all member states, regions, citizens – benefit from keeping the Union as a whole attractive. Not just economically but also from a social and personal perspective.”

As far as Romania’s future development is concerned, Dr. Martin Sieg sees the Eastern European countries catching up and emphasizes that EU membership has helped consolidating democracy, rule of law and market economy in Romania. Nevertheless, the corona crisis in particular will determine the further course, also in Romania.

For Olivia it is already clear what would have to happen for her to return to Romania: “If the opportunity would come for me to work at a certain company with a certain salary that is let’s say exponential better than the one I would get outside the country, I would return, no questions.”

Link to the video: